If you need a reliable, scalable way to grow microorganisms or cells in a controlled environment, a stirred tank bioreactor is often the most practical starting point. This stirred-tank (often shortened to STR) is the workhorse type of bioreactor used across fermentation, biopharmaceutical development, and teaching laboratories because its working principle is clear: controlled agitation delivers efficient mixing, while aeration (when required) supports oxygen transfer and stable growth conditions.

Even when a programme is highly complex—new strains, uncertain broth behaviour, tight product quality targets—this “simple” platform remains solution-oriented because it gives operators direct control over the variables that most affect outcomes: mixing, mass transfer, temperature and pH, and sterility.

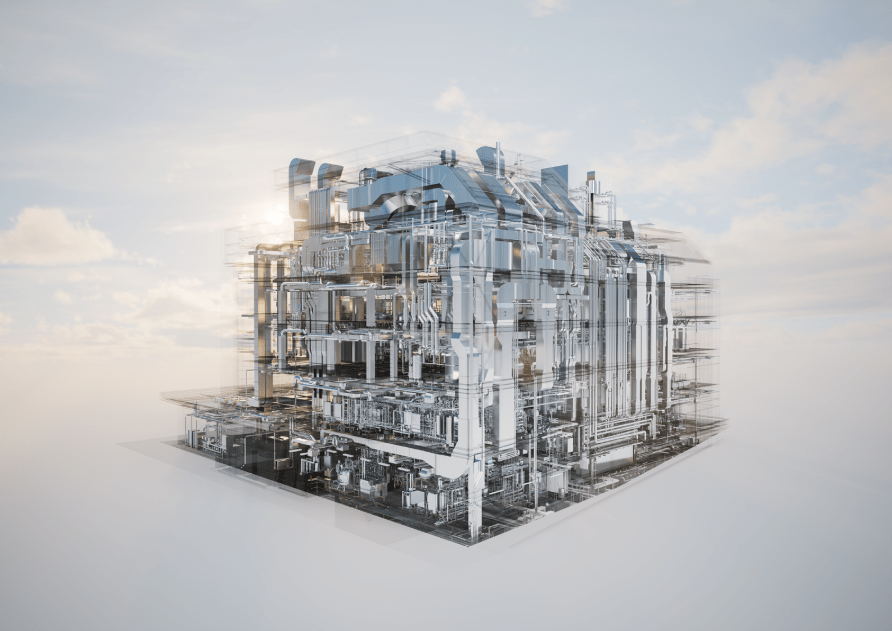

What is a simple stirred tank bioreactor?

A stirred tank bioreactor (also called a stirred tank reactor or stirred-tank bioreactor) is a closed vessel designed for a biochemical process such as cell culture or microbial fermentation. A motor-driven stirrer (agitator) rotates an impeller (or a number of impellers) to keep the bulk liquid homogeneous. For aerobic processes, sterile air or oxygen is introduced via a sparger, forming gas bubbles that are dispersed by mixing to improve gas–liquid mass transfer.

When we say “simple” stirred tank bioreactor, we typically mean a set-up with:

- A single bioreactor vessel with an agitator and one or two impellers

- Standard ports for sampling, additions, and basic probes

- Basic aeration (where needed) and a simple exhaust gas path

- A core control system for temperature control, pH control, and agitation (and dissolved oxygen control for aerobic cultures)

This configuration supports batch and fed-batch operation, and it is sometimes extended to continuous flow/continuous production modes where the process and risk profile justify it. In microbial production, you may also hear the same hardware described as a fermenter or stirred-tank fermenter.

How a stirred tank bioreactor works

A stirred tank bioreactor works by keeping the culture environment uniform enough that cells “see” consistent conditions within the bioreactor.

Mixing, circulation, and concentration control

The impeller(s) create circulation patterns that distribute nutrients, cells, and heat throughout the working volume. This reduces local concentration spikes (for example, near a feed port) and helps avoid gradients in pH or dissolved oxygen that can disrupt cell growth and product formation.

Impeller selection matters because it influences flow and shear. Axial flow designs are often used to drive top-to-bottom circulation, while radial flow impellers can provide stronger local turbulence and gas dispersion. In practice, you tune impeller type, impeller speed, and the number of impellers to achieve sufficient mixing without imposing unnecessary shear forces, especially for shear-sensitive cell culture processes.

Aeration, oxygen demand, and oxygen transfer

For aerobic fermentation and many aerobic cell culture runs, oxygen demand increases as biomass rises. A sparger introduces air or oxygen as gas bubbles, while agitation breaks and disperses bubbles to increase interfacial area and improve oxygen transfer into the liquid phase.

Dissolved oxygen is usually managed using a cascade: a DO setpoint drives changes in agitation, gas flow, and (where used) oxygen enrichment or back-pressure. The objective is stable oxygen availability without excessive foaming or shear—because aggressive sparging can stress some cell lines and increase foam control needs.

Heat transfer and temperature control

Growth and metabolism generate heat—sometimes quickly during peak growth. Heat removal is handled through a jacket and/or internal coil, creating controlled heat transfer from the bulk liquid to the utility side. Under-sized heat transfer capacity can force reduced feeding, lower oxygen delivery, or slower growth, limiting productivity even if everything else is optimised.

Instrumentation, probes, and the control system

Even a “simple” STR relies on stable feedback loops. Typical instrumentation includes:

- Temperature sensor and a temperature control loop

- pH probe and dosing for pH control

- DO sensor (probe) for aerobic cultures

- Optional: foam control sensor, level, and pressure

These sensors feed the control system so the reactor behaves consistently run-to-run—critical when you are scaling from a small vessel to a larger total volume.

Key components in a simple stirred-tank bioreactor

A simple stirred tank bioreactor is defined by a small set of parts that do most of the work.

Bioreactor vessel, headplate, and ports

At small scale (development and training), STRs may be made of glass and designed for autoclave sterilization. At pilot and production scale, the vessel is usually made of stainless steel (commonly 316L) and engineered as a closed vessel for cleaning and sterilization in place (CIP/SIP).

The headplate holds the agitator drive, sampling ports, gas inlets, and probe ports. Thoughtful port layout improves serviceability and reduces dead-legs that can compromise sterilization and increase contamination risk.

Agitation system: agitator, shaft, and impeller blades

The agitation system provides mixing and gas dispersion. Impeller blades are selected for the culture—microbial processes often tolerate higher power input than mammalian cell culture. For shear-sensitive applications, you typically limit tip speed and choose designs that provide circulation without excessive local shear.

Practical considerations include impeller diameter, impeller speed range, the number of impellers, and how well the design keeps cells in suspension (or maintains a homogeneous bulk liquid) across the run.

Baffles

A baffle (or set of baffles) reduces vortexing and converts rotational energy into useful turbulence. Baffles often improve mixing efficiency and oxygen transfer in aerobic microbial fermentation, but they must be designed to support hygienic cleaning and sterilization.

Sparger, aeration, and sterile filtration

The sparger distributes air or oxygen into the liquid phase as gas bubbles. In most systems, the aeration line includes sterile filtration and flow control. Aeration strategy is tuned to the organism: microbial fermentation may prioritise high oxygen transfer, while cell culture often prioritises gentle gas delivery to protect viability.

Exhaust gas path and off-gas handling

Exhaust filters protect sterility and manage aerosols. Off-gas handling may include condensers and pressure control. In more instrumented systems, off-gas monitoring (O₂/CO₂) supports process insight and troubleshooting.

Heat-transfer hardware

A jacket and/or internal coil provides heat transfer. The design must cope with worst-case metabolic heat generation at peak cell density, not just average conditions.

Foam control and antifoam dosing

Foaming is common in aerated fermentation. Foam control can include headspace design, foam probes, and antifoam dosing. Antifoam can protect against overflow, but it can also affect mass transfer and later filtration steps—so it should be treated as a process variable, not a “quick fix”.

Where stirred tank bioreactors are used

Stirred-tank systems are popular because they support a wide range of bioprocessing needs.

- Microbial fermentation: bacteria and yeast processes where oxygen demand, oxygen transfer, and heat removal are central.

- Antibiotic production (process-dependent): many antibiotic and enzyme processes use stirred-tank fermentation because it offers strong control and scalable mixing.

- Bioethanol and industrial bioprocessing: stirred tanks can be used in ethanol fermentation and related biochemical processes where robustness and scaling matter.

- Cell culture (process-dependent): development and some manufacturing where controlled mixing and temperature and pH stability are required.

If you need one reactor technology that can be tailor-made across different runs—different microorganisms or cell lines, different feeding strategies, different oxygen transfer requirements—the stirred tank is usually the default.

Advantages for customers

A simple stirred tank bioreactor delivers practical benefits when you need repeatable performance:

- Reliable control of agitation, temperature control, and (where needed) aeration for consistent run-to-run results.

- Efficient mixing that supports even distribution of nutrients and maintains optimal growth conditions.

- Clear scale-up logic because mixing and oxygen transfer can be measured, tuned, and compared across volumes.

- Straightforward troubleshooting: probes and sensors provide data to diagnose drift in dissolved oxygen, pH, or temperature.

- Flexible operation for batch and fed-batch modes, with extensions possible as the process matures.

Limitations and trade-offs to consider

Even the most familiar reactor design has constraints:

- Shear: high agitation and aeration can generate shear forces that stress shear-sensitive cell lines.

- Foam formation: aerated processes often need foam control and antifoaming strategy, which can influence mass transfer and downstream filtration.

- Oxygen transfer limits: at high cell densities, DO control can become the bottleneck unless aeration, agitation, and pressure strategy are engineered with headroom.

- Heat transfer limits: larger vessels can struggle to remove heat quickly enough during peak growth phases.

These are not reasons to avoid STRs—they are reasons to specify them around the real operating window.

How to choose the right simple stirred tank bioreactor

A “simple” specification is most successful when it is process-led.

Define the process mode and targets

Decide whether you are running batch, fed-batch, or (less commonly) continuous production. Set targets for titre, productivity, cycle time, and acceptable variation in product quality.

Understand organism and broth behaviour

Confirm oxygen demand, shear sensitivity, viscosity changes, and foaming tendency. If solids are present, particle size and suspension behaviour can change mixing needs and impeller selection.

Size mixing and aeration for the worst case

For aerobic runs, design for peak oxygen demand (late growth) rather than the start of the run. Specify the impeller type (axial vs radial), impeller speed range, and sparger strategy so oxygen transfer remains stable without driving excessive foam.

Specify cleaning and sterilization requirements early

At small scale, glass vessels may be sterilised in an autoclave. At production scale, stainless steel systems typically rely on cleaning and sterilization in place. For single-use systems, sterilization is built into the supply chain, but you still need an aseptic assembly and integrity strategy.

Choose the minimum instrumentation that protects consistency

At a minimum: temperature, pH, and DO (for aerobic). Add foam probe, pressure, and level where they reduce manual interventions and contamination risk.

Align upstream with downstream

Harvest method, clarification approach, and downstream filtration/chromatography capacity should influence upstream choices. For example, heavy antifoam use can complicate filtration later, so foam control should be considered end-to-end.

Conclusion

A simple stirred tank bioreactor is the most established and widely used bioreactor format because it combines direct control with broad applicability. It uses mechanical agitation to stabilise mixing, supports aeration and oxygen transfer when required, and provides a clear platform for repeatable monitoring and control. When specified around real microorganism or cell behaviour and worst-case operating conditions, it becomes a reliable, tailor-made foundation for both development and production. For many teams, it remains the most practical route to consistent results in highly complex bioprocessing programmes.