Airlift systems solve a familiar bioprocess problem: how to keep a culture well-circulated and well-aerated without adding an impeller. By using a gas stream to drive fluid circulation, an airlift bioreactor can deliver dependable mixing and oxygen transfer with a low energy requirement and fewer moving parts than a stirred tank bioreactor. That makes an airlift reactor (often shortened to ALR) a reliable option in aerobic processes where shear stress, seal reliability, or maintenance access can become production constraints.

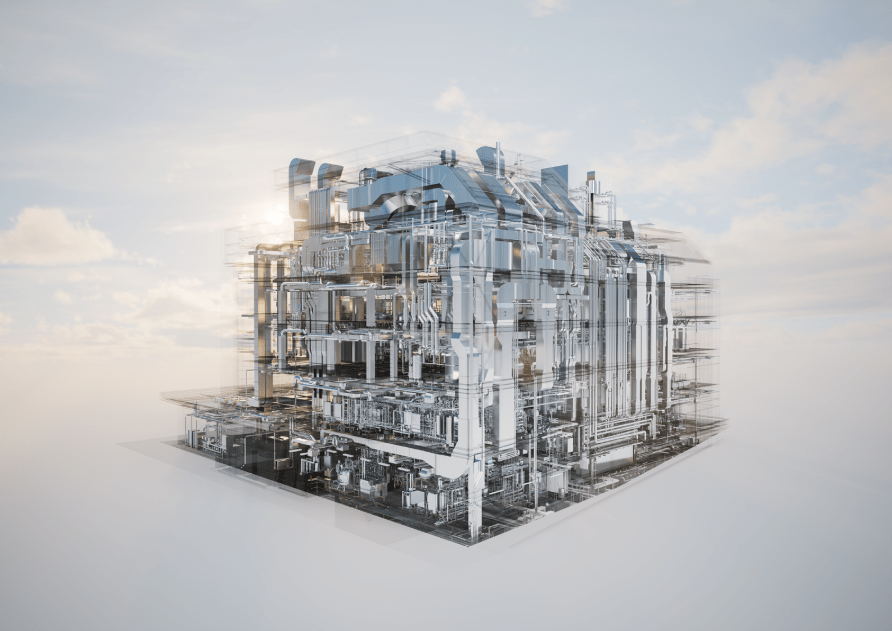

This article is a diagram explained in words. It walks through what you would typically see in an airlift bioreactor diagram—riser, downcomer, sparger, gas separator/disengagement zone—and explains how those zones work together in both internal loop and external loop designs.

What is an airlift bioreactor?

An airlift bioreactor is a gas–liquid bioreactor in which gas injection (typically air or oxygen-enriched gas) reduces the effective density of liquid in one region (the riser), causing it to flow upwards. A connected region with lower gas holdup (the downcomer) stays denser, so liquid returns downward—creating a continuous circulation loop inside the bioreactor.

Instead of an agitator and impeller, the driving force is the density difference between riser and downcomer. When the bioreactor design is right, that loop provides repeatable circulation and mass transfer for a culture of microorganisms (or other biocatalyst systems), often with gentler hydrodynamics than mechanically agitated vessels.

Where airlift reactors sit among types of bioreactors

Airlift systems are one of several different types of bioreactors, and they are often discussed alongside:

- Bubble column reactors: also gas-driven, but typically with less-defined circulation than an ALR.

- Stirred tank bioreactor systems: use mechanical agitation for strong, adjustable mixing across a wider viscosity range.

- Bed bioreactors (including packed bed): may hold a bed of solid particles to support immobilised cells or a catalyst-like biocatalyst (process-dependent).

- Fluidized bed reactors: suspend solids using fluid flow, which can suit certain solids-handling bioprocess windows.

- Membrane bioreactor set-ups: commonly associated with wastewater treatment contexts (term usage varies by application).

- Photobioreactor formats: designed for photosynthetic production such as a culture of microalgae (process-dependent).

The airlift is typically selected when you want a simple design that prioritises gas-driven circulation, low energy requirement, and fewer mechanical maintenance points.

What an airlift bioreactor diagram shows (in words)

Most airlift diagrams label the same core zones, regardless of scale of production:

- Sparger (gas distributor): where air or gas is injected; compressed air is used in many aerobic processes.

- Riser: the gas-rich zone where bubbles rise and most gas–liquid contact occurs.

- Downcomer: the gas-lean return zone that completes the circulation loop.

- Disengagement / gas separator zone (often near the top of the column): where bubbles separate from liquid; off-gas exits.

- Ports and connections: sampling, additions (nutrient feeds), pH control, temperature probes, and harvest/transfer lines.

In operation, bubbles created at the sparger rise through the riser, creating gas holdup (the volume fraction of gas in the liquid). That gas holdup lowers the apparent density of the riser region and drives fluid circulation.

Internal-loop airlift: draft tube layout

In an internal loop airlift, a draft tube is placed inside a single vessel. The draft tube creates two flow zones in the same tank:

- The riser is typically inside the draft tube (gas is sparged there, so gas holdup is higher).

- The downcomer is the annular space between the draft tube and the vessel wall (lower gas holdup).

Because the draft tube defines the loop geometry, internal-loop designs can produce more predictable circulation and mixing than a basic bubble column. In many real processes, “draft tube also” becomes a deciding detail: tube diameter, clearance at the bottom, and the position of the sparger can strongly influence liquid velocity and circulation stability.

What to look for in an internal-loop design

- Draft tube sizing: affects liquid velocity and the pressure difference that drives circulation.

- Sparger placement: should disperse bubbles across the riser to improve oxygen transfer and avoid channeling.

- Disengagement zone sizing: a well-sized headspace/gas separator helps degas the broth and reduces bubble carry-under into the downcomer.

External-loop airlift: pipework loop layout

In an external loop airlift, the riser and downcomer are separated into different legs connected by a pipe loop. Gas is injected into the riser leg; the downcomer leg provides the return.

This layout can make the circulation path more defined and can simplify some scale decisions (for example, changing loop diameter to tune residence time and liquid velocity). The trade-off is hygienic complexity: more external piping and joints can add cleaning and validation load compared to an internal-loop vessel.

What to look for in an external-loop design

- Flow rate stability: external loops can be sensitive to gas rate changes and foaming.

- Degassing control: the top disengagement zone should reliably remove bubbles before liquid returns.

- Cleaning access: external legs and fittings must be designed to clean and sterilise consistently.

How an airlift bioreactor works in practice

Circulation is driven by gas holdup

Airlift circulation is created by density difference: the gas-rich riser becomes “lighter” than the downcomer. This produces a pressure imbalance that circulates the bulk liquid through the loop. In practical terms, that circulation helps distribute nutrient additions, stabilise temperature, and keep the culture more uniform throughout the reactor.

Mass transfer and oxygen transfer depend on bubbles

Airlift performance is often dominated by mass transfer at the gas–liquid interface. Bubble size, gas injection rate, broth properties, and vessel geometry together determine oxygen transfer capability and CO₂ stripping. Because the system uses gas for both aeration and agitation (gas-driven mixing), changes made to meet oxygen demand can also change circulation and mixing behaviour.

Shear profile is different from stirred tanks

Airlifts can reduce shear stress compared with many stirred systems because there is no impeller tip-speed and fewer high-shear microzones. That can be useful for shear-sensitive cultures (process-dependent). However, shear is not “zero”: bubbles, circulation velocity, and local gas–liquid interactions can still affect certain cells.

Temperature and pH control still matter

Airlift does not remove the need for control. Temperature and pH control rely on accurate sensors and effective heat-removal (jacket, coil, or external loop, process-dependent). Because circulation is gas-driven, heat distribution and control behaviour should be evaluated across the full operating window, especially if viscosity changes over time.

Where airlift bioreactors are used

Airlift bioreactors are used in many bioprocessing contexts when the process window fits:

- Aerobic fermentation (process-dependent): gas–liquid transfer and stable circulation without mechanical agitation.

- Wastewater treatment / industrial wastewater (process-dependent): robust operation where continuous aeration is central.

- Microalgae cultivation (process-dependent): certain photobioreactors and gas-driven reactors use airlift-like circulation for photosynthetic cultures.

- Continuous culture concepts (process-dependent): while not the same as a continuous stirred tank, airlift systems can be run continuously if sterility and control requirements are met.

If you are producing a specific metabolite (for example, organic acids such as lactic acid in some pathways), the choice between airlift, bubble column, and stirred systems should be driven by oxygen demand, foam behaviour, viscosity, and downstream sensitivity—not by vessel preference.

Advantages for customers

When engineered around the real broth window, an airlift reactor can be a reliable, tailor-made option:

- Fewer moving parts: no impeller shaft or mechanical seal in the vessel, reducing maintenance points.

- Low energy requirement: circulation is driven by gas injection rather than mechanical agitation.

- Simple design with clear riser/downcomer zones that support predictable circulation.

- Lower shear profile (process-dependent): often attractive for shear-sensitive cultures.

- Scalable circulation concept: internal-loop or external-loop layouts can be chosen to match the process and plant constraints.

Limitations and trade-offs to plan for

- Oxygen-transfer ceiling: very high oxygen demand may require oxygen enrichment, pressure strategy, or a stirred tank format.

- Viscosity and solids sensitivity: if viscosity rises or solids loading becomes significant, gas-driven circulation can weaken and gradients can appear.

- Foam and off-gas load: higher gas rates can increase foam and off-gas handling needs; degassing must be reliable.

- Design sensitivity: draft tube dimensions, loop geometry, and sparger performance strongly affect circulation stability.

How to choose the right airlift bioreactor

- Confirm the culture window: viscosity range, foaming tendency, solids behaviour, and oxygen demand across the full run.

- Choose internal loop vs external loop:

- Internal-loop: compact, often simpler hygienically.

- External-loop: more defined pipe loop circulation, but higher cleaning/validation load.

- Specify sparger performance and cleanability: sparger fouling can change bubble behaviour and oxygen transfer.

- Engineer the disengagement zone: a strong gas separator function helps degas the broth and stabilises circulation.

- Align with downstream and utilities: gas rate, foam control strategy, and any additives can affect downstream separation and filtration.

Conclusion

An airlift bioreactor (ALR) is a gas-driven reactor that uses riser/downcomer circulation to mix and aerate a culture without mechanical agitation. Even without a drawn diagram, the key zones are consistent: sparger (injection), riser, downcomer, and a disengagement/gas separator near the top of the column. When specified for real oxygen demand, flow behaviour, and temperature and pH control needs, airlift systems can be a reliable, low-energy, tailor-made alternative to stirred tanks. The best results come from process-led bioreactor design that balances circulation, mass transfer, foam/off-gas handling, and cleanability across the full operating window.