If you are looking for a reliable way to scale microalgae cultivation without handing control over to weather and chance, a photobioreactor is often the most practical route. It turns light into a manageable input—alongside pH, temperature, and gas exchange—so you can pursue consistent output with fewer surprises. That control can make the difference between promising trials and repeatable biomass production.

What Is a Photobioreactor?

A photobioreactor (PBR) is a controlled cultivation system designed for organisms that require light to grow—most commonly microalgae and cyanobacteria. In simple terms, it is an engineered vessel or loop that supports photobioreactor cultivation by balancing light exposure, CO₂ supply, mixing, and nutrient availability.

Many commercial PBR installations are closed photobioreactors, meaning the culture is contained in tubes, panels, or a sealed vessel with defined inputs and outputs. Compared with open systems (for example, raceway ponds), closed reactors typically deliver tighter control and lower contamination exposure—particularly for higher-value products—although open ponds remain common for low-cost, high-volume algae production.

What a Photobioreactor Does

At its core, a PBR keeps the culture inside a stable operating window so microalgae cells can grow and produce target compounds reliably. It typically enables:

- Light management to reduce self-shading and support stable algal growth

- Mixing and circulation to move cells between light and dark zones

- CO₂ supply and O₂ removal to maintain carbon availability and avoid oxygen build-up

- Temperature control to stabilize cultivation temperature despite solar load or artificial lighting heat

- Nutrient delivery to maintain growth conditions for microalgal growth and product formation

- Monitoring to track trends linked to growth parameters and lipid content (where relevant)

The practical outcome is a controllable environment for the production of microalgae rather than a best-effort outdoor grow.

How a Photobioreactor Works

Photosynthetic organisms convert light energy into chemical energy using CO₂ as a carbon source and releasing oxygen as a by-product. In a PBR, productivity depends on light input, mass-transfer, and nutrient availability—plus how quickly the culture is mixed.

The key limitation is light penetration: as microalgae biomass increases, the culture self-shades and forms steep gradients. A well-designed system supports phototrophic cultivation by cycling cells through illuminated zones so the average exposure remains productive.

Photobioreactor Design Principles

Strong photobioreactor design comes down to a few core design principles: maximize illuminated surface area, keep circulation predictable, and manage gas exchange so oxygen accumulation is controlled (while CO₂ supply remains stable). From a bioprocess and biosystems engineering standpoint, the aim is to align reactor geometry and mixing with growth kinetics, because the same light intensity can produce very different outcomes depending on how often cells move between light and dark regions.

This is also where fouling becomes a real performance constraint. Even thin films on transparent walls reduce light transmission and can slow algae growth, so cleanability must be engineered in—especially for long runs and large-scale operation. In practice, good reactor design is inseparable from design and characterization work: you validate light paths, circulation, degassing, and cleaning strategy against real microalgae in photobioreactors, not only calculations.

Types of Photobioreactors

There is no single best type of photobioreactor. Different photobioreactors suit different targets, footprints, and site constraints, particularly when you compare different types of photobioreactors for lab, pilot, and outdoor use.

Tubular photobioreactor

A tubular photobioreactor uses transparent tubes arranged in loops (often outdoors) to increase light exposure per unit volume. Culture circulates through the tubes using pumps or gas-driven flow.

Why teams choose it: strong light exposure and a proven route for outdoor mass cultivation.

Watch-outs: oxygen can build up in long loops (so many designs include a dedicated degassing section), temperature can swing outdoors, and cleaning can be more demanding across long flow paths.

(In publications and vendor literature you may see “tubular photobioreactors” referenced as a scalable format for continuous or semi-continuous operation.)

Flat-panel and plate photobioreactors

Flat-panel designs use shallow panels to improve light penetration and reduce self-shading. You may also see this family described as a flat plate photobioreactor, flat-plate photobioreactors, or a plate photobioreactor.

Why teams choose it: excellent light utilization and strong productivity potential at higher density.

Watch-outs: scaling often requires many panels (arrays of flat plate photobioreactors), and heat-removal can become a constraint with high-intensity lighting.

For development work, teams sometimes use a glass plate photobioreactor within lab-scale photobioreactor systems to screen strains, test lighting strategies, and define a robust operating window. At pilot scale, you may also see banks of flat panel photobioreactors used as modular “flat photobioreactors” to expand capacity without changing the core geometry.

Column and airlift photobioreactors

Column photobioreactors (bubble-column variants) and an airlift photobioreactor rely on gas flow to drive circulation and CO₂ transfer with fewer moving parts. These are common for indoor installations, where lighting and temperature are easier to stabilize.

Why teams choose it: simpler maintenance and effective gas exchange.

Watch-outs: light penetration still limits scale, so geometry must be tuned to avoid persistent dark zones.

Stirred-tank photobioreactor

A stirred tank photobioreactor uses mechanical agitation like a classic stirred system, with light delivered through transparent walls or internal light sources.

Why teams choose it: strong control of mixing, temperature, and gas transfer—useful for R&D and controlled production.

Watch-outs: internal lighting adds complexity, and agitation can increase shear for some species.

Membrane and hybrid photobioreactors

Some specialized systems combine cultivation with separation, such as a membrane photobioreactor used to retain biomass and intensify the process (application-dependent). These are often described as membrane-assisted PBRs, where a membrane loop (or integrated module) helps separate clarified water while keeping the culture concentrated—an approach more common in environmental or niche process intensification work than in bulk biomass production.

Why teams choose it: improved retention and higher effective cell density in targeted use-cases.

Watch-outs: added complexity and membrane fouling risk.

Open ponds and raceways (comparison baseline)

An open pond is not a closed PBR, but it is often used as a cost-driven baseline for algae production.

Why it is used: low capital cost and simple operation.

Limitations: higher contamination exposure and weather-driven variability, especially when comparing open ponds and photobioreactors side-by-side.

Low-cost closed cultivation formats (bags)

For certain pilot and demonstration set-ups, a low-cost closed approach can include freshwater microalgae in polyethylene bags, which function as simple closed cultivation loops.

Why teams choose it: fast deployment for trials, especially for mass culture of freshwater microalgae.

Watch-outs: lower control and shorter service life than engineered PBRs, with limitations on mixing, heat removal, and long-term reliability.

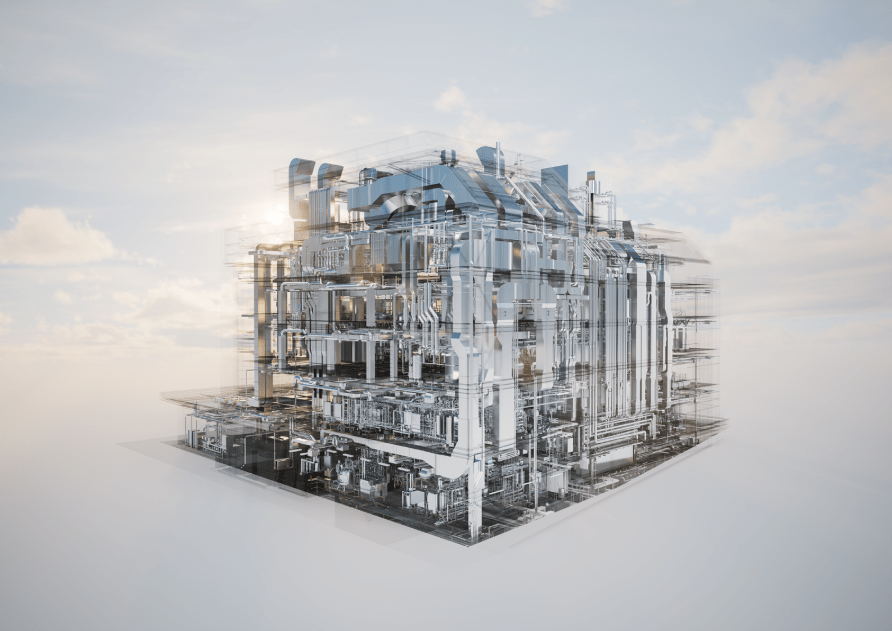

Key Parts of a Photobioreactor

Most algal photobioreactor systems share the same functional building blocks:

- Transparent cultivation surface (tubes, panels, or a vessel wall)

- Light source (sunlight, LEDs, or hybrid systems)

- Mixing and circulation system (pump, airlift, sparging, or mechanical agitation)

- Gas transfer hardware for CO₂ addition and degassing

- Temperature-control (cooling loops, heat-exchangers, or controlled indoor climate)

- Instrumentation (pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, flow, and biomass indicators)

- Cleanability features aligned to fouling and restart cadence

A practical design is not only about growth—it is also about how quickly you can clean, restart, and maintain performance. In other words, a photobioreactor equipped with the right sensors and cleanability features can be the difference between efficient microalgae output and constant downtime.

Benefits of Using a Photobioreactor

Photobioreactors are usually selected because they deliver measurable advantages over open approaches:

- Higher control and reproducibility, supporting consistent output and quality

- Lower contamination exposure due to containment and filtered gas pathways

- Improved productivity potential, especially where light utilization and mixing are optimized

- Better resource efficiency through controlled CO₂ use and nutrient dosing

- Year-round operation for indoor systems that do not rely on seasonal conditions

Common Applications

Photobioreactors have been used across a wide range of applications, from R&D to photobioreactors for mass cultivation. The economic driver differs by sector: high-value molecules prioritize control, while bulk applications must justify cost.

- High-value ingredients and pigments (process-dependent)

- Biofuel production using lipid-rich microalgae biomass (often cost-sensitive)

- Hydrogen production in niche research pathways (highly process-dependent)

- Aquaculture and feed (consistent biomass supply)

- Environmental polishing and integrated nutrient management

- Outdoor photobioreactors for controlled cultivation in outdoor installations

In environmental casework, examples include cultivating Chlorella vulgaris in nutrient-rich wastewater streams for polishing (for example, phosphate uptake), alongside cultivation of Chlorella sp. in controlled systems (process- and site-dependent).

Practical Challenges and Trade-offs

Photobioreactors come with constraints that should be addressed upfront:

- Light limitation and self-shading at higher culture density

- Biofouling on transparent surfaces, reducing light transmission

- Heat management with high-intensity lighting or strong solar load

- Oxygen build-up in dense cultures if degassing is not designed in

- Higher capital and operating cost compared with open approaches

How to Choose the Right Photobioreactor

A process-led selection approach helps avoid underperforming systems:

- Define the organism and product goal

- Which microalgae species are you cultivating (or cyanobacteria)?

- Are you optimizing for biomass, a specific metabolite, or a quality attribute?

- Set targets and operating mode

- Batch cultivation, semi-continuous, or continuous harvest strategy?

- Target concentration, cycle-time, and expected growth rate.

- Decide on light strategy

- Sunlight, LEDs, or hybrid?

- Required intensity, photoperiod, and energy budget.

- Confirm gas exchange needs

- CO₂ demand and addition strategy.

- Oxygen removal and degassing requirements.

- Plan for cleaning and fouling control

- Expected fouling risk and cleaning frequency.

- Access, drainability, and cleaning approach aligned to your site.

- Align with site constraints

- Footprint, utilities (cooling capacity, compressed air/CO₂), and indoor vs outdoor installation.

- Monitoring and data capture requirements.

Conclusion

A photobioreactor is a controlled cultivation platform designed to make light-driven production more predictable. By managing light exposure, mixing, CO₂ supply, and temperature, it helps photosynthetic organisms deliver consistent output with fewer surprises than open approaches. The best system choice is always application-led: high-value products justify tighter control, while bulk algae production demands careful cost and energy optimization. When specified correctly, photobioreactor technology provides a practical path to reproducible, scalable algae cultivation—and unlocks the potential of microalgae where consistency matters.