From life-saving medicines to everyday food ingredients, some of the most valuable products around us begin with something you can’t see: microorganisms doing precise work at scale. A fermenter is the engineered environment that makes that work predictable—turning biology into a repeatable process rather than a gamble. Whether you’re scaling-up a new product or simply want to understand how modern biotech manufacturing functions, it helps to know what happens inside these vessels. Below, we break down the essentials—what a fermenter is, how it works, and how to choose the right set-up for your application.

What Is a Fermenter?

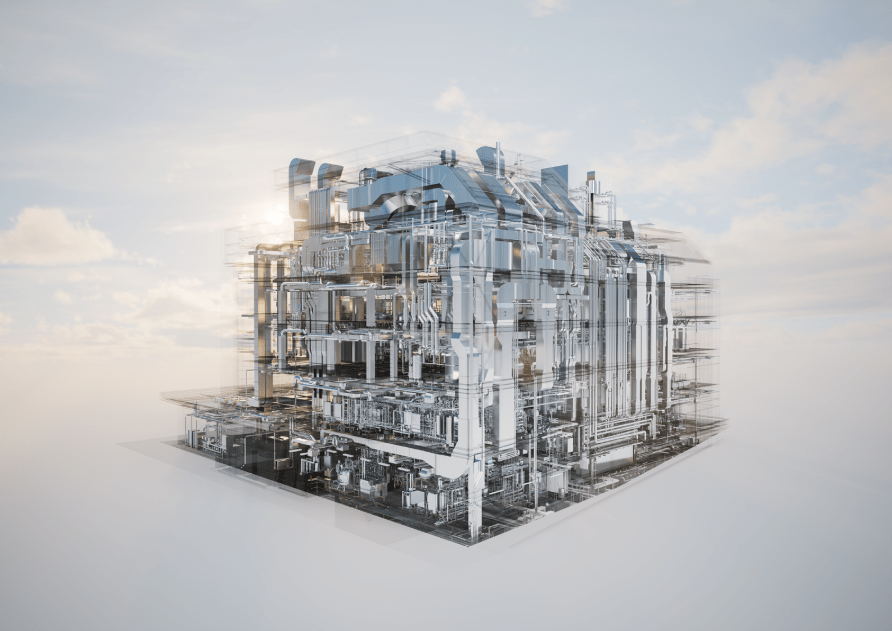

A fermenter is a controlled vessel designed to grow microorganisms—most commonly bacteria, yeast, or fungi—so they can convert raw materials into useful products. In industrial settings, fermenters are used to produce everything from enzymes and food cultures to organic acids, bio-based chemicals, and (in some cases) fuels. What makes a fermenter different from a simple tank is control: temperature, pH, mixing, aeration, and feeding are managed so biology performs predictably and consistently.

Although the term is rooted in “fermentation” as a biochemical pathway, in modern industry it is often used more broadly to describe microbial cultivation for production, including aerobic processes where oxygen-transfer is a key design requirement.

Key Benefits of Using a Fermenter

- Consistency run-to-run: controlled conditions reduce variability and support stable yields. This makes planning easier because you can forecast output more confidently and reduce the risk of unexpected batch losses. Over time, consistent performance also shortens investigations because deviations stand out more clearly.

- Higher productivity: optimized oxygen-transfer, feeding, and heat-removal can increase output. When the system has enough headroom (mixing, gas-flow, and temperature control), you can run more aggressively without hitting oxygen limitation or heat bottlenecks. The result is often higher titre, shorter cycle-time, or both.

- Lower contamination risk: hygienic design and clean-in-place/sterilization-in-place capability support sterility. Fewer manual interventions and well-designed flow paths reduce the chance of contamination entering through sampling points, seals, or poorly drained branches. This protects yield and reduces downtime linked to re-cleaning or batch disposal.

- Scalability: fermenters are designed to scale from pilot to production with predictable performance. With the right mixing, oxygen-transfer, and control strategy, the process can be transferred with fewer surprises as volume increases. This lowers scale-up risk and helps maintain product quality attributes across different vessel sizes.

- Process insight: instrumentation and automation provide data for optimization and troubleshooting. Trend data, event logs, and (where used) off-gas signals help you spot limitations early and understand what changed between batches. That visibility supports continuous improvement and faster root-cause analysis when performance drifts.

What a Fermenter Does

At its core, a fermenter provides an environment where microorganisms can grow, metabolize, and produce a target compound. The system maintains process conditions within a defined operating window so the culture behaves the same way from batch-to-batch in the fermentation process.

A fermenter typically supports:

- Growth control: keeping the culture in the right temperature and pH range. This matters because growth-rate and metabolism can shift quickly when conditions drift, which can change yield and increase by-product formation. In practice, control is achieved through temperature regulation (jackets/coils) and pH loops that dose acid/base (or buffers) in response to real-time measurements.

- Mass-transfer: supplying oxygen (if aerobic) and removing metabolic gases (CO₂). Oxygen-transfer is often a limiting factor in aerobic processes, so fermenters are designed to move oxygen from gas into liquid efficiently while maintaining stable dissolved oxygen. CO₂ removal is equally important because excessive dissolved CO₂ can inhibit growth or affect productivity, so off-gas handling, sparging strategy, and (in some cases) back-pressure are selected with the process window in mind.

- Mixing and uniformity: distributing nutrients, heat, and cells evenly. Good mixing prevents local hot-spots, pH pockets, and feed concentration gradients that can stress the culture and cause performance variability. It also improves control response, because sensors become more representative of the whole vessel rather than one zone. Mixing performance in a bioreactor is set by vessel geometry, baffles, impeller choice (where used), and operating speed, which are crucial for the fermentation process.

- Feeding strategies: batch, fed-batch, or continuous feeding to drive productivity. Feeding is how many processes control growth-rate and product formation—especially in fed-batch, where the goal is to avoid over-feeding that triggers by-products or oxygen limitations. In continuous operation, feeding strategy also governs steady-state stability and washout risk, so flow control and monitoring become critical. The fermenter must support accurate dosing, good feed dispersion, and reliable control logic.

- Foam and pressure control: managing foam events and maintaining stable operation. Foaming is common in microbial processes because proteins, polysaccharides, and surfactant-like compounds accumulate as biomass increases. Left unmanaged, foam can cause product loss, filter blockage, or contamination through exhaust lines, so systems often use foam probes, antifoam dosing, and appropriately sized headspace/off-gas capacity. Pressure control supports stable gas-flow and, where used, can improve oxygen solubility, but it must be engineered safely with suitable relief and off-gas handling.

- Monitoring and data capture: tracking key variables so performance is repeatable and issues are diagnosable. Instrumentation (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, pressure, level/weight, foam, and sometimes off-gas O₂/CO₂) turns fermentation from trial-and-error into a controlled process. High-quality data makes it easier to identify why batches differ—whether it’s sensor drift, feed deviation, oxygen limitation, or a foaming event. It also enables trend-based alarms and continuous improvement, helping teams optimize yields and reduce downtime over time.

Types of Fermenters

Fermenters come in different formats depending on organism needs, viscosity, oxygen demand, and scale. Below are common industrial designs.

Stirred-tank fermenter

A stirred-tank fermenter uses mechanical agitation (impellers) to mix the broth and disperse gas. It is widely used because it offers strong control over mixing, oxygen-transfer, and process uniformity. Because agitation and aeration can be adjusted across a wide operating range, stirred-tank set-ups are often the default choice for pilot-to-production scale-up when flexibility and repeatability matter.

Typical strengths:

- High flexibility across many microbial processes

- Strong oxygen-transfer capability (when designed for it)

- Good control of gradients in larger volumes

Bubble-column fermenter

A bubble-column fermenter relies on rising gas bubbles for mixing, with no mechanical stirrer. It is mechanically simpler and can be suitable for lower-viscosity broths and processes that benefit from gentler mixing. Performance is closely linked to gas-flow and sparger design, so bubble-columns are usually selected when the process oxygen demand can be met without high mechanical energy input.

Typical strengths:

- Fewer moving parts and potentially lower maintenance

- Gentler hydrodynamics for some applications

- Attractive for certain large-volume set-ups

Airlift fermenter

An airlift fermenter is a structured bubble-driven system that creates defined circulation zones (riser/downcomer) to improve mixing consistency compared with a simple bubble-column. This is often achieved with an internal draft-tube or loop geometry that produces more predictable bulk circulation. Airlift designs can be a strong fit when you want steadier mixing than a bubble-column while still keeping shear and mechanical complexity lower than many stirred-tanks.

Typical strengths:

- More predictable circulation than bubble-column designs

- Lower shear than many stirred-tanks

- Useful where gentle handling and consistent mixing are both needed

Packed-bed fermenter

A packed-bed fermenter retains microorganisms on a solid support medium (immobilized or attached cells). These are often used in specialized continuous processes where high cell density improves productivity. Because liquid must flow through the packed structure, design and operation focus heavily on flow distribution, pressure-drop, and fouling control. Packed-bed systems are typically chosen when immobilized-cell operation is proven for the specific conversion and long run-times deliver a clear productivity advantage.

Typical strengths:

- High cell density and stable long run-times (process-dependent)

- Can suit continuous operation in proven applications

- Efficient use of reactor volume in specific conversions

Tower fermenter

A tower fermenter is a tall, high-aspect-ratio vessel format (often a bubble-column or airlift variant) used to support vertical hydrodynamics and footprint efficiency. The taller geometry can increase gas–liquid contact time, which may help in gas-driven mixing set-ups. However, tower designs must be engineered to avoid gradients (temperature, dissolved oxygen, concentration), so heat-removal and monitoring strategy become especially important at scale.

Typical strengths:

- High working volume with reduced floor-space

- Can increase gas–liquid contact time in some set-ups

- Useful where facility layout supports vertical installation

Applications of Fermenters

Fermenters are used across industries wherever microbial conversion creates value at scale.

- Industrial biotech and chemicals: organic acids, amino acids, solvents, and bio-based building blocks. These processes often convert renewable feedstocks (such as sugars) into platform chemicals at production scale, where oxygen-transfer and heat-removal can become limiting factors. Material selection and control strategy are usually chosen to handle wider operating ranges (for example, changing viscosity or pH).

- Food and beverage: yeast propagation, cultures, fermented ingredients, and flavour development. Fermenters help deliver consistent sensory results in fermented foods and beverages by maintaining stable growth conditions that influence flavour, texture, and functional performance. Hygienic design and fast turn-around are often priorities because changeovers can be frequent and product carryover can affect taste.

- Biotech and biopharma (microbial steps): enzymes, intermediates, and microbial-derived products. Many manufacturing routes include microbial cultivation steps to produce high-value ingredients that feed into downstream purification or formulation. These applications typically emphasize repeatability, contamination control, and data capture so batch performance can be traced and investigated.

- Bioenergy: ethanol and other fermentation-based fuels. These are usually high-throughput, cost-sensitive operations where uptime and cycle-time directly affect production economics. Fermenters in this space are often designed for robust operation, efficient heat-removal, and reliable handling of variable feedstocks.

- Environmental and circular processes: waste-to-value applications where microbial conversion is part of the production strategy. Feedstocks can be less uniform and may contain inhibitors or higher solids, so fermenter design often needs stronger solids-handling and fouling resistance. Flexibility in control and cleaning approach can be important to maintain stable performance as input composition changes.

Conclusion

A fermenter is a controlled production vessel that enables microorganisms to convert feedstocks into high-value products reliably at scale. By managing mixing, oxygen-transfer, heat-removal, and core control loops (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen), it supports consistent performance run-to-run across applications from food and beverage to industrial biotech and bioenergy. Choosing the right fermenter means matching vessel type and operating range to your organism and broth behaviour, including viscosity, foaming tendency, and target productivity. With a fit-for-purpose hygienic design, instrumentation, and turn-around strategy, a well-specified fermenter reduces scale-up risk and enables efficient, predictable day-to-day operation.